September 11, 2013:

September 15, 2013 – UPDATE:

I’m happy and excited to report that Ian Heath has sent me his revised CAPTIONS to accompany his artwork from 18 years ago. Over the intervening years he has updated the original captions to incorporate the results of his ongoing research, including having found some new primary sources. I know I speak for all historical miniature wargamers who happen to be interested in the subject of the Afghan Regular Army of the 19th Century when I repeat: THANK YOU IAN!

Though some contemporaries believed that the introduction of uniforms into the Afghan army only began after the First Afghan War, they were already in limited use at least 30 years earlier, and began to ne adopted on a larger scale under the influence of foreign instructors hired during the 1830s. From the outset these uniforms reflected British influence (Elphinstone described Afghan infantry he saw in 1809 as ‘dressed in imitation of our sepoys’), and this remained the case throughout most of the century, even after Russian influence increased during the 1880s.

By the mid-19th century the adoption of Western uniforms was well under way. The majority were initially in the form of condemned and surplus East India Company and, subsequently, British Army stores purchased by the Amir’s agents in Peshawar and other Indian frontline stations, but by the late 1850s native copies were also being made in Kabul. Some time after 1869 Sher Ali formally established his own ‘Army Clothing Department’, which Hensman records as turning out ‘imitation Highland and Rifle costumes, or old Pandy uniforms by the hundred’, including tunics, trousers, kilts, gaiters and even helmets, ‘all neatly made’, as well as pouch-belts, bayonet-frogs and so on made ‘on the English pattern’.(1)

The period from the 1850s through to the end of the Second Afghan War seems to have witnessed the almost universal introduction of uniforms throughout the Afghan regular army. The subsequent decline in their use under Abdur Rahman during the 1880s doubtless resulted from a change in policy whereby soldiers had to buy their own, whereas under Dost Mohammed and Sher Ali uniforms had been issued by the State (theoretically once every two years) and the cost deducted from the soldiers’ pay.(2) Headwear, belt and ammunition pouches were the only items officially issued thereafter (without his military belt ‘a soldier was looked upon as a civilian’), and the everyday dress of soldiers became varied to say the least, a full uniform being provided by the State only in wartime.(3) However, even when full uniforms had been issued with regularity under Dost Mohammed and Sher Ali, the effect was not all that it might have been, Harry Burnett Lumsden observing in 1857 that the use of worn-out and ill-fitting British cast-offs gave Afghan regiments a ‘very slovenly’ appearance.(4)

In addition soldiers didn’t always wear their full uniform anyway, in particular often discarding European-style trousers in favour of native tombons – at the Battle of Charasiab in 1879, for instance, infantrymen are described as being only ‘half-dressed in uniform’, wearing their uniform jackets but not the trousers, which also appears to have been the case with at least some of the troops defending Ali Musjid in November 1878; even Abdur Rahman’s later attempts to stop men wearing their own ‘ugly trousers’ by fining them up to six months’ pay apparently had little effect. Nor were just trousers abandoned, Hensman stating that Afghan sepoys he saw in July 1880 were only recognisable as such from the fact that they wore ‘cross-belts, pouches and bayonets’, while in 1878 a Russian officer, Grodekoff, mentioned that his Afghan cavalry escort ‘donned their red uniforms and dress caps’ only when approaching Herat at the end of the march.(5)

The figures portrayed in the twelve plates here are only a small, but hopefully representative, selection of the numerous uniform variants to be found in contemporary sources.

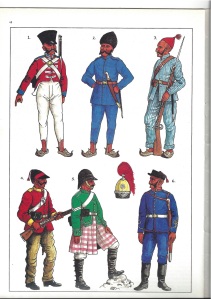

Plates 1-6

1. Infantryman 1857

This figure is reconstructed from descriptions given by Henry Bellew, who saw several infantry regiments at Kandahar, each distinctively attired in a mixture of British cast-offs and locally-made copies.(6) One wore red jackets, and another a ‘drab-coloured uniform of European pattern’, while a third seems to have had a different uniform for each company – one company wore blue jackets, black trousers and white forage-caps, with white cross-belts so dirty they were almost brown; another wore red jackets, white trousers, cross-belts and ‘old-fashioned shakos’; a third was ‘clothed in a uniform of drab-coloured cloth throughout’.

Bellew several times mentions the Afghans’ preference for red uniforms, stating that ‘the red coat is held in the highest estimation by the Afghan rulers, and is equally dreaded by their subjects’. He claims that in every expedition the army was ‘always furnished with a contingent … dressed in red coats and shakos’ because of the morale effect they had on the enemy. The Central Asian traveller Vambéry, ay Herat shortly after its capture by Dost Mohammed in 1863, also mentions that the Afghan soldier’s ‘favourite garment is the red English coat, from which, even in sleep, he will not part’.(7)

Bellew, Vambéry and, in 1872, Marsh(8) all mention the shortness of Afghan infantrymen’s trousers. ‘The cut of these seemed to be regulated on principles of the strictest economy,’ observed Bellew, ‘for they were, in each instance, some four or five inches too short, and were secured below the foot by long and conspicuous straps of white cloth, to prevent their being drawn too high up the leg.’ Vambéry mentions that the Afghans he saw ‘might have been mistaken for European troops, if most of them had not had on their bare feet the pointed Kabuli shoe, and had not had their short trousers so tightly stretched that they threatened every moment to burst and fly up above the knee.’ Marsh simply says that ‘their trousers were too short, but well strapped down’.

Bellew also describes the uniform of a regimental band seen at Kalat-i-Ghilzai, consisting of ‘dirty yellow trousers, with a broad stripe of bright green down the legs, and drummers’ jackets and shakos. They looked more like a troop of harlequins than military musicians’.

2. Herati Infantryman 1860

In addition to the central Government in Kabul, the virtually autonomous rulers of provinces such as Herat and Balkh had uniformed, Westernised regular troops of their own – indeed, those of Balkh were influential in Dost Mohammed’s decision to modernise his own army – and the civil war of 1864–69 saw uniformed troops on both sides, as too did the fighting for Herat in 1863, when Dost Mohammed captured the town. Vambéry describes Dost’s own regulars seen at Herat that year as still wearing shakos, but these were dropped in favour of the Herati beehive-shaped hat – worn by uniformed Herati regulars by 1837 at the latest – very soon afterwards, This was henceforth the preferred headwear of the Afghan military until the 1880s, and could be of lambskin or felt, though the native hat from which it was copied, as worn by such local tribes as the Jamshidi and Hazara, was invariably the former. Usually they were coloured. C.E. Yate describes those he saw being worn by troops in 1886 as like small, brown, felt beehives, sometimes having ‘a small tassel at the top and a black band round the bottom, with now and then a rosette on one side’.(9)

A translated Russian work, the Military Statistical Compendium for 1868,(10) provides details of the dress of Herati infantry at the end of 1860 as ‘a bright blue coat spun from some light cotton material and cut in the English style with long skirts, stand-up collar, and metal buttons; pantaloons also of some cotton material, tight and very short with stripes [sic – probably a mistranslation of ‘straps’; see caption to Figure 1]. Foot-coverings are slippers worn over the naked foot. Head-dress on service is the cone-shaped Persian hat; in quarters the red pointed skull-cap for old soldiers, yellow ditto for recruits. There is no difference in the uniform, &c, of the several regiments.’ He says that armament comprised flintlock musket, tulwar and a 12in–18in knife. The knife remained a popular – if unofficial – weapon amongst Afghan infantrymen for the rest of the century.

3. Kabuli Infantryman 1872

Both Marsh and Bellew(11) record details of Afghan garrison troops seen in Kandahar in 1872, the most interesting of whom were a Kabuli regiment wearing ‘a tight jacket and trousers, cut on the old English pattern’, which were made from a local striped woollen cloth described as resembling bed-ticking – i.e. the material used at the time for mattresses and pillows (for those to young to remember it, the traditional English bed-ticking that Marsh and Bellew had in mind, which survived in use into the mid-20th century, was traditionally off-white, in fact almost blue-grey, with narrow dark blue stripes and a tendency to look grubby). Cross-belts and pouches were brown leather, while their headdress was a conical, quilted red kullah with a tuft of red or scarlet wool fixed to the point. Marsh considered that the absence of turbans gave their shaved heads ‘a very bare, cold appearance’. Of the other two regiments Bellew saw, one wore red jackets and the other (a Kandahari unit) ‘a uniform of dingy yellow ochre’, perhaps indicating a form of khaki.

The shaven head was characteristic of the Muslim Afghans at this date. Shaving off the beard, however, along with the wearing of side-whiskers and often a moustache too, were imitations of British practice. Lumsden in 1857 considered that shaving off the beard was ‘in order to render the recognition of a deserter more probable’.

4. Infantryman 1878

Travelling through Afghan Turkestan just as war was about to break out between Sher Ali and the British, Grodekoff’s descriptions of the uniforms he saw are particularly valuable. At Mazar-i-Sharif guardsmen at the Governor’s residence were seen wearing red tunics with yellow facings, collars and cuffs, white cotton ‘knee-breeches’ (indicating either short trousers like those of plates 1 and 2, or else native trousers), ‘shoes but no stockings’, and a felt helmet with a metal star on the front, doubtless the native copy of the British helmet referred to in the captions to plates 5 and 8. Belts worn round the waist and over the shoulder, both supporting ammunition pouches, were of white leather.

The garrison at Maimana seems to have particularly struck Grodekoff, since he observes that ‘a greater set of guys [in the mid-19th century dictionary sense of ‘persons of grotesque looks or dress’] than the infantrymen would have been difficult to have found in any European pantomime. Their uniforms were made up of such a medley of colours and shapes, and sat upon them so badly, that it was impossible not to laugh at them.’ He records the uniforms coming in various colours – red with yellow ‘trimmings’ (presumably facings); blue with red or raspberry collars and cuffs; and black ‘with white cuffs, white collars, white buttons, and white facings’. Head-dress consisted of either a turban or a striped cotton ‘helmet’, described as low, with a peak coming down close over the eyes and resembling a Bashkir tubeteika, with ‘a small bunch of feathers on the top’. Yate describes such hats seen at Mazar-i-Sharif in 1886 (where they were being worn by both infantry and cavalry) as ‘imitation Russian caps of dirty black cloth, with a red band and a huge peak, generally wrongly put on; and the cap, being worn well pulled down over the head, looked more like a shapeless nightcap than anything else.’

Other references to infantry uniform colours during the period 1878–80 can be found scattered through contemporary British official documents and accounts of the Second Afghan War. An official report, for instance, records that one of the mutinous regiments in Kabul in 1879 wore black; R. Gordon-Creed saw at Gandamak a company ‘dressed in khaki with black facings, and small black caps’,(12) while Ayub Khan’s regulars at Maiwand are described by an officer of the 66th as having been dressed ‘in red and blue’ – doubtless meaning red jackets and blue trousers.(13) Waller Ashe records two prisoners taken in July 1880 as wearing ‘the ragged remains of what was once a picturesque and workmanlike uniform consisting of dark purple turban, grey tunic, and well-worn knickerbockers’,(14) while at the Battle of Kandahar in September Howard Hensman saw some soldiers wearing ‘dark-coloured jackets, and turbans surmounted by small yellow pompons, such as were worn long ago by European armies’, and others ‘clad in khaki’ who, since they were almost mistaken for Indian infantry, presumably all wore turbans (the use of which steadily increased from this time on).(15) Shoulder-straps, incidentally, at least sometimes bore a regimental number, Joshua Duke recording the numbers ‘2’ and ‘3’ being seen on the shoulders of Afghan casualties at Charasiab in October 1879.(16)

5. ‘Highland Guard’ 1879

The best description of the uniform worn by this unusual unit is to be found in The Graphic illustrated newspaper of 26 July 1879, which says they were ‘dressed in a dark green tunic, cut after precisely the same fashion as our own Scotch contingent, with a long skirt of the Macgregor tartan reaching below the knee; beneath this white drawers, gaiters, and native shoes. Their head-dress is a felt helmet, of no pretty pattern, covered with drab khakdir.(17) All the men shave their chins, wear short mutton-chop whiskers, and moustache.’ Note in particular that their tunics are here described as green, and not red as might have been expected (and, indeed, as they are portrayed in two volumes of Osprey’s ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, one of which – apparently drawing on an unspecified contemporary source, which I have not myself encountered during my research – states in addition that their facings were yellow).(18) This may be explained by the fact that there was more than one such unit, the so-called ‘Highland Guard’ being one of the three Ardali(or ‘Orderly’) regiments. Mitford, however, gives quite different dress for the latter, categorically stating that a dark brown uniform with red facings, and not a kilt, ‘conclusively proved’ a soldier’s connection with the ‘Orderly’ regiments.

Though variously described by contemporaries as being Mackenzie or Macgregor tartan, the pattern of the kilt was apparently not really (or not always) tartan at all, two Scots officers at Gandamak in 1879, after arguing the point heatedly for some time, eventually agreeing to describe it as ‘Rob Roy’. Nor was it necessarily even a kilt: Yates describes it in 1885 as simply ‘a piece of checked cloth in red and blue squares’ worn round the waist ‘like a towel’, while somewhat later Frank Martin describes the ‘kilts’ worn by an Afghan bagpipe band he saw as ‘represented by a check print shirt, which hangs below the tunic and outside the trousers’. Nor was the check pattern always the same, Gordon Creed recording that the kilts of guardsmen he saw at Gandamak were ‘made of different colours’, while photographs show that some didn’t have a check pattern at all. Afghan infantry helmets, invariably described as made of felt, were less refined in appearance than the British ones from which they were copied – Yate describes one he saw as ‘mushroom-shaped’ (see also the descriptions given in the caption to plate 8) – though as we saw in Grodekoff’s account above, some likewise had a metal badge on the front. On at least one occasion helmets are recorded being worn over a turban.

6. Artilleryman 1878–85

As early as 1857 Lumsden states that Afghan regular gunners were ‘clothed in our old artillery uniforms’; whether he is alluding to East India Company artillery or British Army artillery uniforms isn’t clear, but since he was an officer of the EIC the former seems more likely. In 1879 the men of a mountain battery accompanying Yakub Beg are recorded wearing blue uniforms and brass helmets, so it is tempting to imagine that these may have been at least based on the dress of the old Bengal Horse Artillery; BHA helmets were certainly worn by a guard cavalry regiment seen by Lord Roberts the same year (see the caption to plate 8).

Mitford describes artillerymen’s helmets abandoned along the Afghan line of retreat after the Battle of Charasiab as being well-made, ‘with plated mounts and a red horsehair plume, the plate in front bearing three guns and a Persian inscription.’ After the Battle of Peiwar Kotal in December 1878 J.A.S. Colquhoun similarly records that in the Afghan artillery camp ‘the gunners had left their silver-mounted brass helmets and forage caps’,(19) while Charles Robertson mentions that ‘black forage-caps, with red tufts, lay strewed about in all directions.’(20)

The main source for the figure in this plate is a picture in the Illustrated London News of 16 May 1885, recording a durbar between Abdur Rahman and the British at Rawalpindi in April that year, at which Abdur Rahman’s escort included an Afghan mountain battery. W.J. Honner, who was present, records the gunners’ dress on this occasion as ‘somewhat similar to our own mountain battery dress, the cap being particularly striking – a dark blue band tipped with a red cap identical in shape and material to an ordinary football or yachtsman’s cap’.(21) The shoulder-strap arrangement securing his sword-scabbard may only have been introduced in the 1880s. The sword itself is a Cossack shashka(for which see the caption to plate 8).

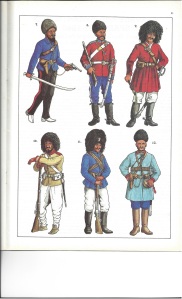

7. Officer 1878–80

That the dress of Afghan officers took sundry forms is apparent from the most cursory examination of the sources. Even in 1857 Lumsden noted that ‘officers of all grades, even of the same regiment, presented themselves in every imaginable British costume’, Bellew likewise observing that ‘they seemed to have no particular uniform, as each was dressed in a costume … regulated by the individual tastes and ideas of what a military uniform should be.’ The dress of four officers he saw at Kalat-i-Ghilzai that year consisted respectively of: a forage-cap worn with a Royal Navy tail-coat; a scarlet shell-jacket, white trousers and a civilian black silk hat; an undress military frock coat and a bushy fox-fur hat; and a general in ‘an entire suit of white calico, cut in the English fashion into frock-coat, waistcoat, and trousers’, topped off by a general’s cocked-hat complete with its plume of white feathers. These are extreme examples, however, and by the 1870s most officers’ uniforms were – with the inevitable exception of those worn by generals – more restrained. Even so, Yate in 1885 observed that ‘the officers of both cavalry and infantry were dressed according to their own individual fancy, without the slightest reference to the uniform of their men’ – which is confirmed in passing by Gordon Creed, who records the officers of a khaki-uniformed regiment seen in 1879 as wearing scarlet jackets.

The figure depicted is based on numerous contemporary pictures and Grodekoff’s description of the officers he saw at Mazar-i-Sharif in October 1878. Yakub Khan, whilst Governor of Herat in 1872, wore virtually identical dress, consisting of ‘a European military braided blue coat’, black trousers, and sheepskin Herati hat.(22) Normal armament for an officer was a revolver or pistol and a sword of British, Afghan or, later, Russian provenance. Note that unlike the rank and file, officers generally retained their beards. Colquhoun describes the officers of a cavalry regiment in 1879 as being dressed ‘very much the same as the men, but the colonel … was dressed in an old staff tunic with gold embroidery’; Duke says that he wore ‘a full-dress scarlet coat covered with gold lace’.

8. Cavalryman 1879

Several detailed descriptions of Afghan regular cavalry confirm the general accuracy of the picture from which this figure is taken, published in the Illustrated London News of 18 October 1879. Joshua Duke, for instance, says that ‘a slovenly scarlet coat, loose blue trousers, tucked carelessly into dirty boots without spurs, white pouch-belts and accoutrements, a sword, carbine, and last, but not least, a Kabul short-handled riding-whip, formed their uniform. Each trooper wore a hideous slate-coloured helmet of an ugly shape.’ Colquhoun, describing the same contingent, says they were ‘dressed in old British red cloth uniforms with white belts, more or less clay-piped, rather baggy blue cotton trousers, with long boots innocent of blacking. The only purely native article about them was their headdress, which, however, was also a copy of the present English helmet, but being made rather shapeless, of a soft grey felt, it was not becoming.’ He adds that the whip was stuck into the right boot when not required, and also that a large number of men carried eye shades (‘great pieces of cardboard apparently covered with cloth, and fitted to the helmet above the peak, shading either the side or the front of the face from the sun, as required’), which were slung round the neck when not in use. Both of these accounts, it will be noted, refer to helmets, but pictures of such cavalrymen in the Illustrated London Newsinvariably show them wearing the Herati hat depicted, described by A. Le Messurier(23) in this context as ‘dyed sheepskin, with the wool outside, covering a large felt skull-cap’. The ILNalso shows spurs being worn, despite Duke’s specific statement to the contrary.

In severe weather Afghan regular cavalry wore sheepskin poshteens just like their Anglo-Indian counterparts, who, as can be seen, they resembled rather closely (H.C. Marsh actually describes a troop he saw at Kandahar in 1872 as ‘got up in imitation of our native cavalry’). This similarity is most clearly demonstrated by a description of a cavalry skirmish at Ghul Kotul in January 1879: ‘At a distance it was impossible to distinguish [the Afghans] from our own native cavalry, and when close they could only be known by a peculiar fur cap, like a small bearskin with a red scollop of cloth in front over the forehead. Their poshteens were the same as those worn by the native cavalry, the carbine was slung, they wore swords and long boots, and the horse accoutrements were in the same style as our own cavalry’.(24)

We know from various such references that saddles and harness were British, that a ‘cloak’ (doubtless a native choga) was rolled up in front of the saddle, with a couple of saddle-bags and a rolled-up blanket or similar behind. Grodekoff provides some additional equipment details, telling us that ‘the metal portion of the cartridge pouches and belts bear English marks and inscriptions, such as “First Bengal Regiment of Light Cavalry”, “God save the Queen”, and so forth.’ He adds that in addition to a sabre and carbine each dafadarcarried a six-foot lance with a small pennon.

Alternative cavalry uniforms mentioned in the sources include Lord Roberts’ reference to a detachment of what appears to have been the Risala-i-Shahiguard regiment in July 1879, who were ‘dressed something like British Dragoons’ except that they wore ‘discarded helmets of the old Bengal Horse Artillery’;(25) and Bellew’s reference to a regiment seen at Kandahar in 1872 which wore ‘blue hussar-jackets, top-boots, and scarlet busbies’ (a confirmation in passing that the Herati hat was sometimes coloured). Grodekoff similarly came across regulars wearing ‘Hungarian hussar jackets’ at Maimana in 1878. Yate in 1886 briefly describes the dress of several cavalry regiments, including one dressed and armed exactly as depicted while others wore brown jackets, blue trousers, long boots and a cap like that of plate 4, and in addition to a carbine carried a curved sword described in The Graphic of 30 May 1885 as a copy of the Cossack shashka, having no guard so that all but an inch of the hilt fitted ‘well into the scabbard’, which was slung from rings fitted to the convex side of the curve. A correspondent to the Illustrated London News confirms that cavalry uniforms in 1885, as in 1878–80, were mostly either red or blue.

9. Herati Cavalryman 1879

Cavalry regiments raised in Herat and Afghan Turkestan were generally attired in Turcoman rather than Afghan fashion. Their quite different appearance can be seen in this plate, from a picture in the Illustrated London News of 27 September 1879 depicting two such troopers. The original caption describes them as wearing ‘large black sheepskin caps, the long hair of which came down over their eyes and face, giving a wild look to the wearers. They said that this was the Turcoman style of headdress, and that it was common with the troops of Herat and along the northern border of Afghanistan.’ In May that year a deserter from such a regiment (stationed in Kabul) is similarly described as wearing ‘an immense brown fur cap, about the size of a Grenadier’s bear-skin. His uniform was a red cloth tunic, but over this he wore a choga, which concealed it.’

An illustration in The Graphic of 30 May 1885 depicts a group of what it describes as Uzbek lancers, who are very similarly attired to this figure, albeit in jackets that are more obviously military, having shoulder-straps, upright collars and buttons. However, Uzbeks (nicknamed ‘House-Bugs’ by the British) more usually wore a turban wrapped round a peaked cap – indeed, the uniforms of two Uzbek regiments in the 1890s are specifically referred to as being distinguishable by their ‘violet caps with black peaks’ – and in 1885 there were theoretically not yet any Uzbek units in the Afghan regular army, so these are perhaps actually Turcoman lancers, or else Uzbek irregulars. Rudyard Kipling also calls one of the cavalry regiments in Abdur Rahman’s escort at Rawalpindi as ‘Usbeg Lancers’; these wore ‘mustard-hued coats’ and ‘shaggy caps’. Yate describes a regiment of Turcoman lancers raised in Afghan Turkestan, that he saw in Kabul in 1886, as wearing ‘huge sheepskin hats’, blue coats and blue trousers, and carrying green-painted lances ‘so long that they had no lance-buckets to their stirrups, but had to order [them] on the ground.’ Their lances had blue-and-white pennons.(26)

10. Infantryman 1885

This soldier is one of those who fought the Russians at Tahkepri in Penjdeh, from a picture of General Ghaus-ud-Din Khan and his troops in the Illustrated London News of 16 May 1885, which shows other men wearing turbans similar to those of Indian troops. Yate provides assorted details of infantry at this date, observing, for instance, that ‘happy is the Afghan who can swagger about in the British soldier’s red tunic’ (noting in passing how many different English county regiments’ badges might be seen on these), but that it was difficult to distinguish regiments from one another on parade ‘as only a portion of the men were clad in uniform’, even though most wore the ‘regulation felt hat’. The only uniform colours he specifically mentions are red, and ‘dirty khaki coats and white trousers’. Two infantry regiments seen by Kipling at Rawalpindi the same year wore ‘white duck trousers, European boots, and a tunic of blue with red trimmings’.

Contemporary pictures indicate that Afghan soldiers now generally wore beards and no longer shaved their heads, some actually being shown with quite long hair, though this may have depended on ethnic background. Why or when these changes came about is not apparent.

11. Cavalry Guardsman 1885

This man is from sketches in The Graphic of 9 May 1885 and the Illustrated London News of the following week, depicting Abdur Rahman’s escort at the durbar at Rawalpindi. The colours come from a description in the latter, which also shows that the huge sheepskin hat had an extension shaped somewhat like a beaver’s tail hanging down the back. Infantry guardsmen at much the same date are described by a Russian traveller as wearing white or khaki trousers; red jackets with white piping, white or yellow collars, yellow or red shoulder-straps, and buttons ‘bearing the English State emblem’; shoes with turned-up toes; and ‘leathern helmets’ with a brass ‘English emblem’ on the front.(27) Though obsolete British equipment was therefore still in widespread use, an English officer present at Rawalpindi noted that Afghan uniforms seen there ‘bore a decidedly Russian cut’, contemporary pictures showing numerous Russian features such as bandoliers, round fur caps and the widespread use of tall boots by infantrymen. (Kipling, however, tells us that their knee-high boots were abused so badly by the men – who only pushed their feet halfway in, or ‘wrenched the heels sideways’ etc – that he wondered how on earth they had managed to struggle all the way from Kabul in them.)

12. Officer 1886

This picture of an officer encountered in Afghan Turkestan comes from a book by the French traveller Bonvalot,(28) who describes his hat as similar to a Turcoman’s but with the hair shaved off, and therefore of wool rather than felt. His belt and sword were of English origin, and he was armed in addition with a pistol, a knife and a breech-loading rifle ‘similar to that carried by sergeants in the Anglo-Indian army.’ A junior officer encountered shortly before was dressed very much like plate 10, but instead of the Turcoman hat wore a peakless, fur-bordered cap wrapped in a small turban, while his slightly longer jacket was black with a red collar.

NOTES:

(1) Howard Hensman, The Afghan War of 1879–80, 1881.

(2) Sources of the 1870s and later refer to the deduction of one month’s pay per annum for clothing. H.B. Lumsden in 1857, however, mentions ‘two months’ deduction annually’ (Peter S. Lumsden and George R. Elsmie, Lumsden of the Guides, 1899).

(3) M.A. Babakhodjayev, ‘Afghanistan’s Armed Forces and Amir Abdul Rahman’s Military Reform’ Afghanistan XXIII, 1970. An eye-witness confirms that their clothes were ‘of any sort and pattern as the wearer may desire or his purse can afford. Some have old English army or railway coats; others have coats of various colours and materials which have been made in the bazaar.’ (Frank A. Martin, Under the Absolute Amir, 1907). With the exception of guardsmen, photographs dating to the 1890s generally show Afghan soldiers wearing shirts, loose native trousers, assorted woollen jackets, and turbans wrapped round kullahs.

(4) Lumsden and Elsmie, 1899.

(5) N. Grodekoff, translated by Charles Marvin, Colonel Grodekoff’s Ride from Samarcand to Herat, 1880.

(6) H.W. Bellew, Journal of a Political Mission to Afghanistan in 1857, 1862.

(7) Arminius Vambéry, Travels in Central Asia, 1864.

(8) Hippisley Cunliffe Marsh, A Ride Through Islam, 1877.

(9) C.E. Yate, Northern Afghanistan, 1888.

(10) Quoted in L.N. Soboleff’s The Anglo-Afghan Struggle (translated by W.E. Gowan), 1885.

(11) H.W. Bellew, From the Indus to the Tigris, 1874.

(12) William Trousdale (editor), The Gordon Creeds in Afghanistan 1839 and 1878–79, 1984.

(13) Quoted in J. Percy Groves, The 66th Berkshire Regiment, 1887.

(14) Walter Ashe, Personal Records of the Kandahar Campaign by Officers Engaged Therein, 1881.

(15) Distinguishing friend from foe was inevitably a problem where one side had gone out of its way to imitate the dress of the other, and numerous similar incidents can be found. Lord Roberts, for example, describes how at Peiwar Kotal in December 1878 Afghan infantry were ‘dressed so exactly like some of our own Native soldiers that they were not recognised until they got within 100 yards.’ See also caption to plate 8.

(16) Joshua Duke, Recollections of the Kabul Campaign, 1879 & 1880, 1883.

(17) R.C.W. Mitford describes guardsmen he saw in Kabul in October 1879 as wearing black helmets, and other sources mention them being white. To Caubul with the Cavalry Brigade, 1881.

(18) Robert Wilkinson-Latham, North-West Frontier 1837–1947, 1977.

(19) J.A.S. Colquhoun, With the Kurram Field Force, 1878–79, 1881.

(20) Charles Gray Robertson, Kurum, Kabul and Kandahar, 1881.

(21) W.J. Honner, ‘An Afghan Mountain Battery’ Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine II, 1885. We have to be very grateful to Rudyard Kipling, who was also present, for a priceless piece of information: he tells us that the carriages of the battery’s guns were painted ‘dull green’ – a vital detail provided in very few accounts of indigenous Asiatic armies. Newspaper reporter Kipling’s observations are quoted extensively in Neil K. Moran, Kipling and Afghanistan, 2005.

(22) Marsh 1877.

(23) A. Le Messurier, Kandahar in 1879, 1880.

(24) Le Messurier, 1880. So similar were British and Afghan cavalry, in fact, that Mitford notes that whereas initially the British had removed the scarlet-and-white pennons from their lances they subsequently felt the need to restore them ‘as a distinguishing mark’.

(25) Lord Roberts of Kandahar, Forty-One Years in India, 1897. Bengal Horse Artillery helmets, similar in shape to those of French cuirassiers, were very distinctive, being painted black, with gilt fittings, crest and chin-strap, and a scarlet plume.

(26) Uzbeks were not often taken into the regular army, being generally regarded by the Afghans as ‘effeminate and unsuited for war’ (the Uzbeks of Maimana apparently being considered an exception). Most of the few who were conscripted were employed in the capacity of officers’ servants, camel drivers and so on, though Grodekoff met two who were officers. However, even though the first Uzbek regiments were raised only at the beginning of the 1890s, Uzbek irregulars, consisting largely of lance-armed cavalry (the lance being usually about 12 feet long), had been around since Dost Mohammed’s time.

(27) B.L. Tageyev, Our Neighbours in the Pamirs, quoted in Babakhodjayev, 1970.

(28) Gabriel Bonvalot, Through the Heart of Asia vol.I, 1889.

© Ian Heath 2013