Welcome to the new version of Maiwand Day.

Today, July 27th 2020, is the 140th Maiwand Day. The 140th Anniversary of the 1880 battle. After ten years maintaining MaiwandDay on blogger.com, I am migrating to this website of my own here at MaiwandDay.com. My older daughter/middle child Isabella did all the work making this possible, for which I give her my tremendous and sincere thanks! It took her a while but she finally got around to it while she was home from West Point on extended Spring-into-Summer Break, due to the COIVD-19 pandemic. So in addition to having her back home with our family, I got a special bonus out of the awful circumstances of these past four months. We dropped her off at the airport last night and she took the red-eye flight back to school, from whence she just reported testing Negative for COVID-19, which is good news as she will not have to stay in the quarantine barracks for the next two weeks or more. We will miss her but it’s good for her to be back where she belongs at this point in her life, preparing for her future and continuing to learn how to do her part defending our country.

The main reason I wanted to move the site was to improve the search function. I am still in the process of tagging all posts from the past decade to fit into the CATEGORIES I’ve created, which are visible on the right side of this page. Hopefully this will make it much easier for visitors to find whatever they might be looking for. When I’m done tagging all the posts I will let you know.

Meanwhile, I have something new to share. It’s a 25 page document with information on Afghan Military Flags, mostly from the 19th Century, but with some info on earlier and later eras. It’s always been difficult for me to find illustrations or written descriptions of flags carried by Afghan regulars and Afghan and North-West Frontier tribal forces in battle, so I’ve gathered together all the bits and pieces of such info — both written and illustrated — that I’ve come across over the years and now make it available to anyone who may find it useful.

This process started by accident when I tried to order a few Tribal flags from “Flag Dude” Rick O’Brien, who told me he’d been getting requests for NWF/Afghan flags but had only semi-historical and Hollywood inspired designs in the 50 flag “NW Frontier” collection. He’d recently been doing a lot of work on a new “Flags of India” collection, starting with Mughal and Sikh flags from the 18th and early 19th Century. Since my interest is more focused on later 19th Century Afghan and North-West Frontier enemies of the British Empire, he asked if I could send him whatever info I had on hand. One thing led to another and this 25-page reference document is the result. I wish it contained more and better written descriptions and more and better illustrations, especially of Afghan regular Army flags from 1878-1880, during the Second Afghan War, but we must take what we can get. Maybe my amateur efforts and offerings will inspire someone with better skills and resources to get us more and better info. But until then, I think this is better than nothing.

I am presenting the entire doc here on this site as text and images, but I’m also attaching it as a DOWNLOAD at the end of this post, so you can download the info for use offline if you think it would be useful.

AFGHAN MILITARY FLAG INFO from Mad Guru – 07.27.20

This document contains information I’ve collected on Afghan military flags over approximately the past 20 years. It has some cool images that historical wargamers can use to create Afghan and Northwest Frontier flags, BUT it only includes a handful of definitively historically accurate flags. The images are accompanied by my own historical background & source info, but the first 4½ pages are a 2012 article on Afghan military flags w/footnotes & sources by Iranian Studies scholar Habib Borjian, Senior Assistant Editor at Encyclopedia Iranica (http://iranicaonline.org).

(1) ii. MILITARY FLAGS OF AFGHANISTAN

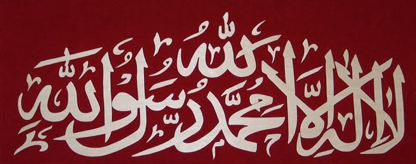

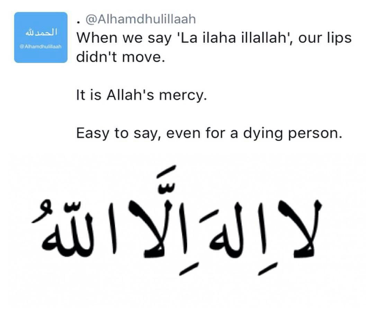

The Kingdom of Afghanistan. Almost nothing is known about the flags of Afghanistan during the reign of the Sadōzay dynasty and the early decades of the Moḥammadzay dynasty. Traditionally, nonstandard flags of different colors were used in wars. In the reign of Amir Dōst Moḥammad (1819-63) and Šēr ʿAlī Khan (1863-79; see AFGHANISTAN x) there existed triangular, red and green military flags bearing the words of the Islamic confession of faith (šahāda) as well as the names of the four caliphs and verses from the Koran relating to jehād “holy war,” all in white color (Gubar et al., p. 99-100; for illustrations depicting scenes of Anglo-Afghan battles with Afghans holding military flags, see, e.g., Roskoschny, pp. 20, 28, 308-9; Adamec, pp. 153, 198). The earliest Afghan flag shown in vexillological books of the 19th century has green-white-green horizontal stripes (Flaggen-Almanack, Hamburg, n.d. [1940s?]). A similar flag is illustrated under “Kauff. Afghanistans” (Afghanistan merchant flag) in the chart Official-Atlas aller Standdarten Kriegschiff-…und Handerlflaggen, Bremen, n.d. (ca. 1948; see also note by W. Smith in Gubar et al., p. 99).

In the reign of Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan (r. 1880-1901), black became the standard color of the royal/national flag. Contemporary stamps and coins reveal the formation of a modern coat of arms which became a persistent symbol on the national flags for coming decades: a temple/mosque flanked by two flags, inside of which are a meḥrāb (prayer niche) and menbar (pulpit). The arms were surrounded by muskets, sabres, cannon, and it appears in white on the black flag (“Bayraq”). This arms appeared on the national flag (PLATE IX a) used during the reign of Amir Ḥabīb-Allāh (1901-19). Nevertheless, there were a number of other, military and civilian, flags in use, especially by the members of royal family. The royal flag had a red field bearing the name of the king in a white ṭoḡrā (Gubar et al.; Smith; cf. “Bayraq”).

After the War of Independence of 1919, King Amān-Allāh (r. 1919-29; q.v.) abolished all personal and civilian flags as a gesture of the centralization of the nation’s power. The new flag (PLATE IX b) added the royal shako (kolāh) on the top of a somewhat differently stylized mosque, now topped by a dome, and two crossed swords beneath. The whole was placed within a circle (at times an oval; see “Bayraq”) surrounded by rays forming an eight-pointed star, which may have been imitated from the similar pattern featured in the royal flag of the Ottoman Empire (Smith, p. 352, n. 2). Similar arms were in use as early as 1912 (on the coins; see Smith, p. 352, n. 3) and their rendition on the flag varied in detail, e.g., cannon barrels or rifles were substituted for the swords (cf. the Afghan national flag appearing on the cover of the booklet titled Afḡānestān ḥokmodārānenek mamlakatmazī zīāratlarī ḵāṭeralarī, published following King Amān-Allāh’s visit to Turkey in 1928, where an open book, apparently the Koran, appeared immediately above the swords). This flag, though not mentioned in the first constitution of Afghanistan (1923), may be regarded as the first “national” flag of the country, as it was the first to gain international recognition.

Another version of the emblem was introduced in 1926 on coins, stamps, and occasionally appeared on the national flag (PLATE IX c), which omitted the shako, weapons, and the surrounding eight-pointed star, but which framed the central mosque from below with a crescent-shaped wreath (Sykes, II, pp. 304-306; Smith, p. 342). This emblem appears to have had quite limited usage during Amān-Allāh’s reign, yet it was the prototype of the coat of arms in use during 1931-74 (see below). The flags of the army, called ʿAlam-e mobārak, were also black, both sides of which were crowded with religious inscriptions and the phrase Dawlat-e ʿellīya-ye mostaqella-ye Afḡānestān “The exalted independent Government of Afghanistan” (PLATE IX d; “Bayraq”; for illustrations see Gubar et al, pp. 102-4).

On 2 September 1928, the lōya jerga, the national tribal assembly, approved a new national flag that had three vertical stripes of black, red, and green, with a new coat of arms consisting of two sheaves of wheat, a chain of golden mountains, and a star and rising sun (PLATE IX e; cf. a reconstructed illustration of the arms shown in Vexilla Nostra, no. 91, Sept.-Oct. 1977, p. 49, which includes the word Afḡānestānon a ribbon). This flag not only replaced the religious symbolism of the former flags by a modern arms but also adopted the conventional tricolor background, typical of European national flags since the French Revolution. Even Amān-Allāh’s interpretation of colors was inconsistent with the traditional concepts: “In the new flag, black represents our past, red the bood shed for the independence, and green is a symbol of wealth and hopes for the future” (New York Times, 5 September 1928). The flag was indeed a clear expression of the lofty reforms proposed by the king following his European trip. The flag, like the reforms, had a short life and was abolished in January 1929, when the king abdicated. The civil war that broke out brought to power Ḥabīb-Allāh Bačča-ye Saqqā (q.v.), who restored the 1919-26 national flag during his short rule.

Nāder Shah’s (1929-33) policy of moderate reforms was reflected in the flag he reportedly used when he seized power (PLATE IX f; Gordon, p. 218; Wheeler-Holohan, 1933). It was the tricolor flag introduced by Amān-Allāh just a year before, now bearing the old coat of arms surrounded by an eight-pointed star in white. The arms, however, was soon modified as a bound sheaf of wheat circling a stylized representation of a mosque, which also recalls the architectural characteristics of the mausoleum of Aḥmad Shah Dorrānī (q.v.) in Qandahār. Below was the name Afḡānestān in nasḵ script and the date 1348 (1929, the year Nāder Shah seized power; see Afghanistan Ministry of Information and Culture, p. 11). Another interpretation proposed later on that year was the date of the adoption of the flag itself (see e.g. “The Afghan Flag,” Afghanistan News 4, December 1960, p. 17). The flag was described in Article 4 of the Constitution of 1931 and was reconfirmed in the Constitution of 1964, in which the proportions of 2:3 were legally specified. The flag remained similar during the long, stable reign of Moḥammad-Ẓāher Shah (1933-73); yet as presented in various illustrations, the white coat of arms sometimes encroached on the black and green stripes (PLATE IX g), but, most often, it was contained entirely within the middle red stripe. There have been different interpretations of these colors; e.g. the black stands for the religious and historical heritage of the country, the red for the national struggle for independence, and the green for peace, hope, progress and prosperity (Afghanistan Ministry of Information and Culture, pp. 4-5; cf. Encyclopedia Americana II, 1966, p. 322).

Meanwhile, the Afghan tribes residing in the Northeasten Frontier Province of Pakistan had been using various flags as symbol of their struggle for uniting with Afghanistan. Photographs in a booklet entitled Paštūnestān and authored by a certain Bēnavā (in the late 1940s?) exhibit flags used by various Pathan groups: usually with a white inscription in nasḵ script reading Allāh akbar, Paštūnestān, or Paštūnestān zenda bād, on a red background. In various years of the 1960s and 1970s, the Afghan government issued a set of postage stamps commemorating the idea of Paštūnestān. The flag (PLATE IX h) is red with a seal on a black vertical stripe, surrounded by the inscription Allāh akbar and Paštūnestān. The circular seal is blue, circumscribed by a white band, with three green, snow-tipped mountain peaks, behind which rises an eleven-rayed sun (Smith et al.). A flag with a different design was introduced ca. 1985 for the putative Paštūnestān.

Republic of Afghanistan. As Afghanistan became a republic under Moḥammad Dāwūd Khan (1973-78; q.v.) following a coup d’état, a new national flag was introduced on 9 May 1974, in which the same national colors were arranged horizontally (PLATE X a). In the upper hoist was a new coat of arms in gold and brown: a stylized eagle bearing on its breast the combined meḥrāb and pulpit from the former emblems; thus the religious element still present, but shrunken considerably. The eagle was said to have lived in the lofty mountains of the country and symbolized its sovereignty. The wreath of wheat-ears represented the occupation of most of the citizens, i.e., agriculture. The ribbon now bore the Pashto title Da Afḡānestān jomhūrīyat “The Republic of Afghanistan” and the date of the republican coup d’état, 26 Čongāṧ (Saraṭān; see CALENDAR iii) 1352 (17 July 1973). The colors of the flag were now interpreted as follows: black (top) as representative of the historical national flag which was used particularly in the third Anglo-Afghan war in 1919 (q.v.); the red (middle) as a symbol of valor and sacrifice; the green, occupying the lower half of the flag, as prosperity (“The Flag Law in Afghanistan,” Afghanistan 27/1, Spring 1974, pp. 1-11.) Another interpretation of the colors was the progress from the dark times of the past to prosperity, and of the eagle as representing the legendary bird who brought the wheat crown to Jamšīd, the first king of Ārīānā (i.e., ancient Afghanistan; Barraclough and Crampton, pp. 188-89; The Flag Bulletin 13/2, 1974, pp. 31ff.), and—ironically for a republic—the first Afghan king, Aḥmad Shah Dorrānī (W. Smith, Flags and Arms Across the World, New York, n.d. [ca. 1980], p. 16).

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. After the revolution of 27 April 1978 a red flag with a golden emblem on the upper hoist was adopted (PLATE X b), apparently after the Soviet example. The five-pointed star at the top of the emblem was said by the Marxist government (of Ḥafīẓ-Allāh Amīn, leader of the Ḵalq faction of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan [PDPA]) to stand for the five main “nationalities” of the country. In the center was inscribed ḵalq “masses” in nastaʿlīqscript. The Pashto words on the ribbon read: Da Ṯawr enqelāb 1357 da Afḡānestān demōkrātīk jomhūrīyat “The April revolution 1357 (Š./1978) of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan” (“Hoisting the Red flag,” The Kabul Times, 19 October 1978, p. 2; see also the three articles on the flag in the 19 October 1979 issue of the newspaper); Flaggenmitteilung, no. 26, Oct. 1978; The Flag Bulletin 18/1, 1979, pp. 3-7).

Another coup d’état on 27 December 1979 brought to power Babrak Kārmal, who belonged to the rival Parčam “flag” faction of the ruling PDPA, and who tried to dissociate his administration from the atheistic position taken by his predecessor. In his flag inauguration speech (“The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan’s Tricolor Flag Reflects the Will [and] Traditions of Our People,” Afghanistan 33/1, Spring 1980, pp. 1-7), Kārmal did his best to draw on religious, patriotic, and historical values in order to interpret the new flag, which was essentially the revival of the traditional black-red-green flag (PLATE X c). The black now represented the banner of Abū Moslem (q.v.), who had led a revolt in Khorasan (interpreted as the medieval word for Afghanistan) against the Omayyad caliphs. The red color was said to be that of the Ghaznavids, the rulers of the first local Islamic dynasty, who, as ḡāzīs “religious warriors,” carried Islam into the Indian subcontinent. Green was said to be a general color for all Muslims. The new emblem which appeared on the top hoist and was surrounded by wreaths of wheat (an element of former flags) consisted of an open book, under the familiar icon of the meḥrāb and pulpit, a rising sun, and, above all, a five-pointed star flanked by two segments of a gear (representing industry; The Flag Bulletin 19/6, 1980, pp. 331-36). Through its traditional symbolism, the new flag signified the sovereignty of the country and especially its independence from the Soviet Union.

This emblem was modified under Najīb-Allāh, whose National Front government tried to separate itself from the Marxist ideology of the Party (PLATE X d). Thus the word “democratic” was dropped from the official name of the republic, as the red star and the book (which had been identified as a symbol of scientific and cultural revolution; ibid) was eliminated from the coat of arms (Constitution of the Republic of Afghanistan [of 30 November 1987], Kabul, n.d., p. 5). The ruling party (PDPA), however, adopted a red flag with a golden cogwheel surrounding an ear of wheat in the upper hoist—apparently to appease the secular feelings of its members (“Republic of Afghanistan,” The Flag Bulletin 27/6, 1988, pp. 204-15).

Islamic Afghanistan. On 28 April 1992 when Islamic rebels took Kabul and the civil war began among the rival factions, forces in Kabul used a flag of three equal horizontal stripes in green, white, and black (top to bottom), substituting white for the red color of previous flags. The flag was made official in December 1992 with the inscription: Allāh akbar (top stripe), lā elāh ellā Allāh Moḥammad Rasūl Allāh(middle stripe; PLATE X e; The Flag Bulletin, no. 151, 1993, p. 88).

But the inscription was soon incorporated into and replaced by a coat of arms which now stands in gold in the center of the flag (PLATE X f). This new emblem resembled that used by the royal family: a mosque (stylized somewhat differently) flanked by two flags appears in the center above the date 1771 [Š./1992]. It was framed by sheaves of wheat circled by a ribbon. The name of the state appeared in the bottom in Pashto: Da Afḡānestān eslāmī dawlat. The two crossed sabers which encircled the bottom and sides, of the emblem were new design elements (The Flag Bulletin 32/1, 1993, no. 153, p. 176). The individual groups of the Islamic coalition had their own flag (Flaggen mitteilungen, no. 213, pp. 2-3).

The Ṭālebān, who captured Kabul after a lengthy siege in September 1996, had long been operating under a plain white flag. The words of the šahāda in green were added to it, and it was used as a national flag possibly in October 1997, simultaneously with the change in the name of the country to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (The Flag Bulletin 36/5, 1997, pp. 184-85.

Bibliography:

L. W. Adamec, Dictionary of Afghan Wars, Revolutions, and Insurgencies, Lanham, Md., 1996.

Afghanistan Ministry of Information and Culture, The Afghan Flag, Kabul, 1968.

E. M. C. Barraclough and W. G. Crampton, eds., Flags of the World, London, 1978.

“Bayraq,” in Dāʾerat al-maʿāref-e Ārīānā IV, Kabul, 1962, pp. 3304-7.

Ḡ.-M. Ḡobār (Gubar), “Bayraq dar Afḡānestān,” Ārīānā 1/9, 1321 Š./1942.

W. J. Gordon, Flags of the World, London, 1930.

G.-M. Gubar et al., “A History of the Symbols of Afghanistan,” The Flag Bulletin6/3, 1967, pp. 91-105.

P. C. Lux-Wurm, “A Vexillological Tour of Afghanistan,” The Flag Bulletin 18/1, 1979, pp. 17-20.

H. Roskoschny, Afghanistan und feine nacharlander, Leipzig, n.d. (ca. early 1900s).

W. Smith, “National Flags of Modern Afghanistan,” The Flag Bulletin 19/6, 1980, pp. 337-59.

W. Smith, T. Greene, and L. Loynes, “Flags of Hope: Pakhtunistan,” The Flag Bulletin 4/2, 1965, pp. 32-33.

P. Sykes, A History of Afghanistan, 2 vols., London, 1940.

V. Wheeler-Holohan, Manual of Flags, London, 1933.

(Habib Borjian)

Originally Published: December 15, 1999

Last Updated: January 31, 2012

This article is available in print.

Vol. X, Fasc. 1, pp. 27-32

Cite this entry:

Habib Borjian, “FLAGS ii. Of Afghanistan,”Encyclopædia Iranica, X/1, pp. 27-32, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/flags-ii (accessed on 31 January 2012).

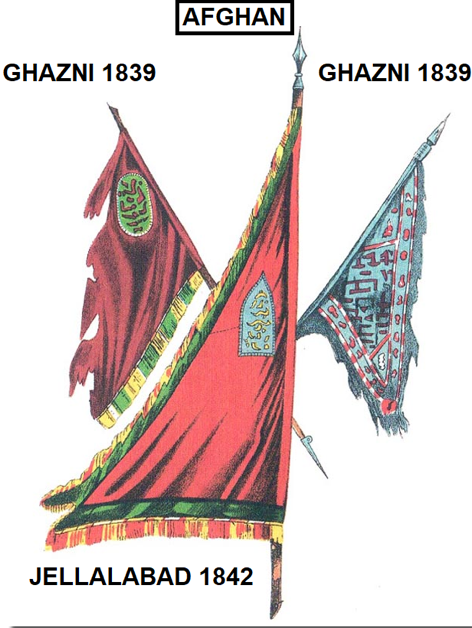

(2) ILLUSTRATION OF AFGHAN FLAGS from the Archives of the Somerset Light Infantry, labelled “Ghazni 1839” & “Jellalabad 1842”:

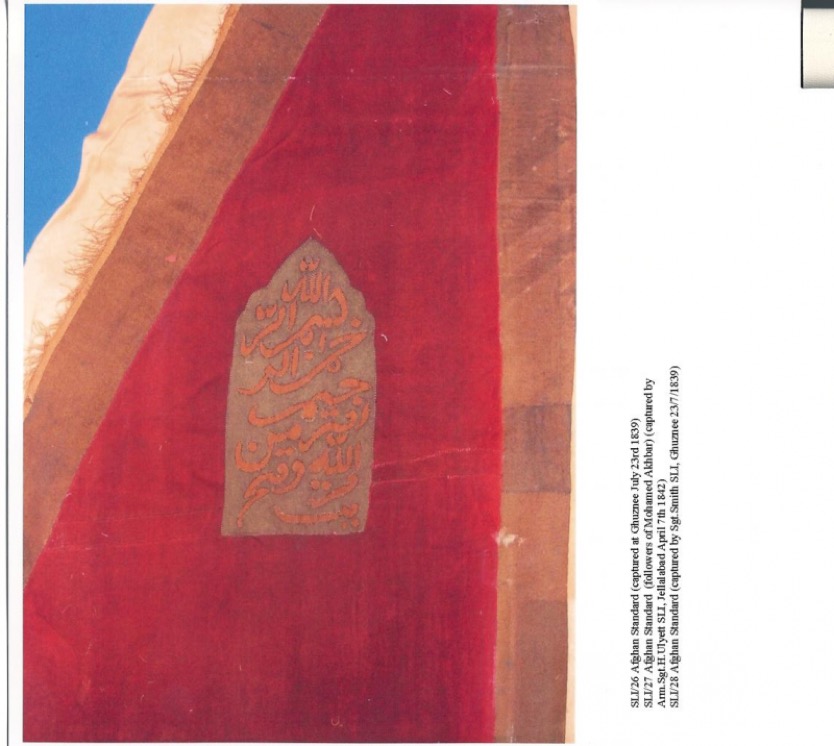

(3) SOMERSET LIGHT INFANTRY MUSEUM FLAG #1:

Above is a photo of an Afghan flag from the Somerset Light Infantry Museum. Under their prior regimental title as the 13th (1st Somersetshire) Regiment (Light Infantry) the regiment fought in Afghanistan during the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-1842). Their Commandng Officer, Colonel Sir Robert Sale, was an important British officer whose wife, Lady Florentia Sale, became the most famous British prisoner of the war after publishing a memoir of her captivity. I have turned the photo to what I believe is its proper orientation, because seen this way the writing on it is recognizable as the Islamic statement of faith (AKA: the Shahada):”There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger” in ARABIC. It seems likely the flag in this photo was the source for the Afghan flag in the illustration labelled, “JELLALABAD 1842”, since the design is virtually identical, the only significant difference being the coloring of the border fringe.

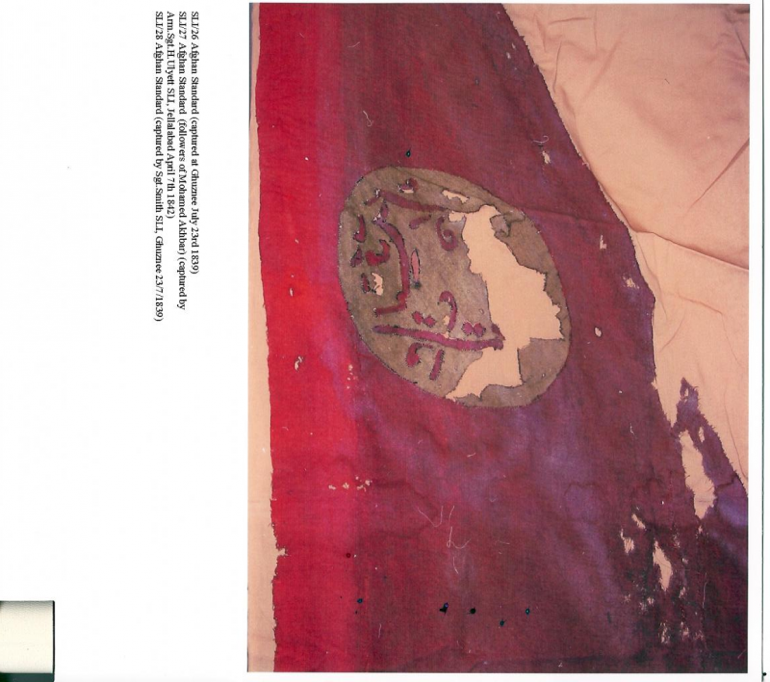

(4) Below is a 2nd photo from the same Somerset Light Inf. museum, which I believe was the source of one of the archive illustration images labelled “Ghazni 1839”. I’m certain the damaged decoration within the circle is Arabic script. I don’t read Arabic but after consulting with a native Arabic speaker I believe it is the NAMES OF THE FOUR CALIPHS arranged facing each other within the circle – one each at top, bottom, left & right. The first four caliphs of the Islamic empire – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali are referred to as Rashidun (“rightly guided”) Caliphs (632-661 CE) by mainstream Sunni Muslims, and occupy a place of special eminence and honor in their tradition.

Like the previous photo, this flag appears to have only 2 colors, the RED triangular field and the possibly faded YELLOW or GOLD, or possibly darkened by dirt over intervening 180 or so years, WHITE circle, which bears the Arabic inscription in the same red as the field. I’m no expert on textile color deterioration, but to my layman’s eye it seems unlikely that the bright green color in the archive illustration was ever the color of the circle in this flag. My guess is that it was added to that illustration to make it more colorful/visually interesting. But of course that’s just a theory, and it’s possible that 180 years ago, when those illustrations were made, the flags did include the various other bright colors.

(5) Here are two contemporary descriptions of AFGHAN TRIBAL FLAGS in use during the Second Afghan War of 1878-1880:

- A written description from the battle of Charasiab, on page 24 of the first edition of “TO CAUBUL WITH THE CAVALRY BRIGADE” by Major R.C.W. Mitford of the 14th Bengal Lancers:

So: RED, WHITE, DARK-BLUE, GREEN, and YELLOW tribal flags, which were generally but perhaps not always triangular in shape. Based on the other info in this document these flags could be: A PLAIN SOLID COLOR or INSCRIBED IN ARABIC WITH VARIOUS ISLAMIC PHRASES and possibly/probably FRINGED in either the same or a contrasting color.

- The painting, “92nd Highlanders storming the Asmai Heights, 1879” by William Skeoch Cumming, a Scottish artist known for painting military and Scottish historical subjects, who served with the 19thCompany, Imperial Yeomanry in the Second Boer War. Because he both specialized in military subjects & personally served in action, I think it’s fair to assume he did due diligence when researching the details in this painting. One good example is the 1857 “Pouch-Belt” equipment and banderole greatcoats worn by the Highlanders, which is historically accurate but not generally seen in other period artwork:

(3) Here’s a slightly later visual of a TRIANGULAR FLAG from the Second Afghan War, from page 267 of the 1895 British book Illustrated Battles of the Nineteenth Century, volume 1:

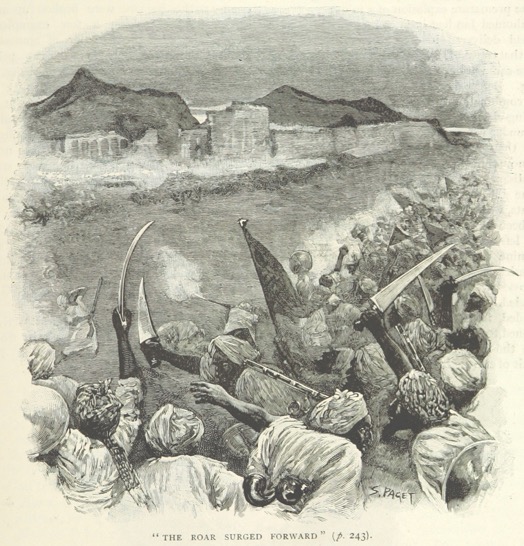

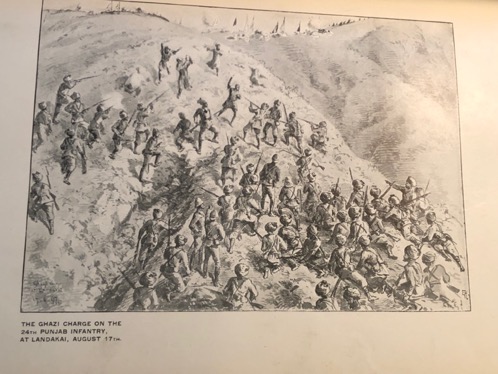

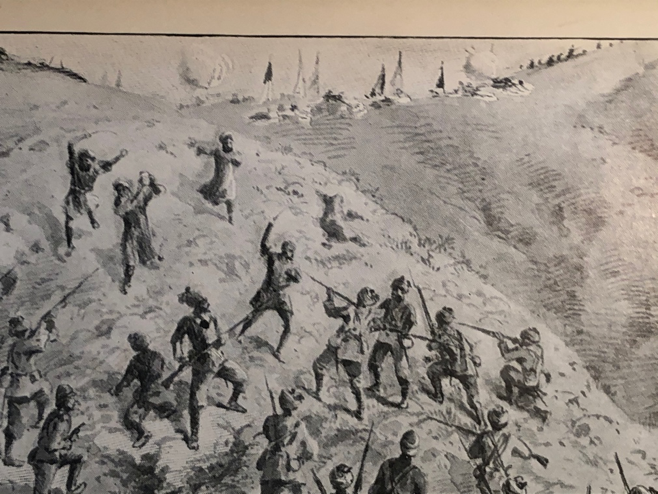

(4) TRIANGULAR TRIBAL FLAGS from “Sketches on Service During the Indian Frontier Campaigns of 1897,” written & illustrated by Major E.A.P. Hobday, Royal Artillery, who saw the subjects of all his sketches with his own eyes…

Page 43 features an illustration of a Ghazi charge, shown below:

A close look at the top of the sketch reveals a large number of TRIANGULAR FLAGS carried by the Tribal forces on the hilltop:

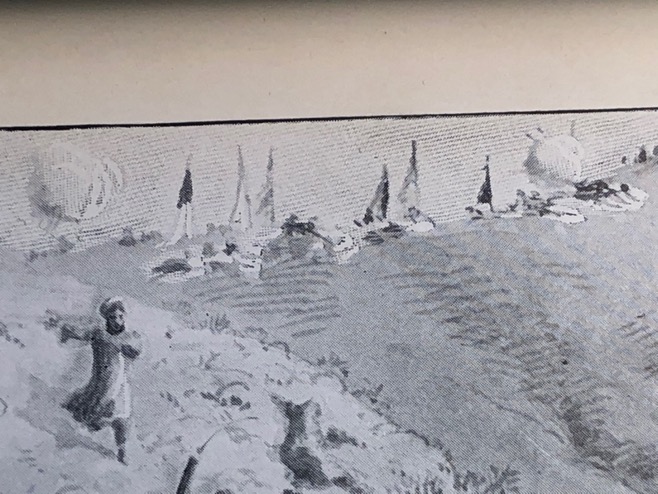

(5) As the timeline proceeds we get this c.1919 photo showing a collection of Afghan tribesmen or “tribal militia” led by 4 standard-bearers around the time of the Third Afghan War. As seen in the photo, all 4 of the flags are triangular, in keeping with probably the most common detail used in various written descriptions of “Pathan” flags, banners, and standards by British military writers throughout the 19th Century.

Now we’ll turn the clock back and focus on more “official” Afghan dynastic and governmental flags…

(6) From 1709 to 1738 almost all of modern Afghanistan was ruled by the HOTAK DYNASTY. They flew a SOLID BLACK FLAG:

They are also said to have flown black flags inscribed with the Shahada in white.

(7) The Hotak Dynasty was overthrown by Persian King and conqueror of Afghanistan, Nader Shah. After Nader was assassinated back in Persia, Ahmad Shah Durrani, an Afghan officer of humble origin who had risen under his command went home with 4,000 fellow Afghan soldiers-of-fortune, conquered the country for himself and became the first Amir of modern Afghanistan (ruled 1747-1772). It’s generally accepted that the Durrani dynasty (1747-1823/1842) used this green/white/green horizontal tricolor as what could be called the “national” flag of Afghanistan:

(8) Another Durrani flag is this white sword on black background:

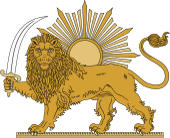

(9) PERSIAN/IRANIAN/QIZILBASH of Afghanistan:

Across the border in Persia/Iran another type of flag was in common use by Nader Shah and other Persian rulers before and after him. It featured the “Lion and Sun” motif:

Nader Shah’s ethnic background was QIZILBASH (“Red Heads”) which includes a variety of militant Shiite groups, some of Turkic origin. Here’s a quote explaining the link between the Persian soldiers who carried this flag and their direct descendants in Afghanistan:

The Afshār and Qājār rulers of Persia who succeeded the Safavids, stemmed from a Qizilbash background. Many other Qizilbash – Turcoman and Non-Turcoman – were settled in far eastern cities such as Kabul and Kandahar during the conquests of Nader Shah, and remained there as consultants to the new Afghan crown after the Shah’s death.

Qizilbash in Afghanistan live in urban areas, such as Kabul, Herat or Mazari Sharif, as well as in certain villages in Hazarajat. They are descendants of the troops left behind by Nadir Shah during his “Indian campaign” in 1738.[45][46] Afghanistan’s Qizilbash held important posts in government offices in the past, and today engage in trade or are craftsmen. Since the creation of Afghanistan, they constitute an important and politically influential element of society. Estimates of their population vary from 30,000 to 200,000.[47][48] They are Persian-speaking Shi’i Muslims.

During the 18th Century enough Persian Qizilbash permanently settled in Afghanistan for them to make up the majority of Afghan regular artillery crews 100 years later during the 1878-1880 war. Though there is no historical evidence, this Persian-Afghan military connection makes me think it’s not out of the question for an occasional 19th Century Afghan Tribal or regular army unit to carry flags featuring the “Lion and Sun” insignia, on a green, red, or white background. Such units would have troops of Qizilbash back-ground, and/or hail from places like Herat or Farah (near the border with Persia/Iran).

(10) There’s also this tricolor standard used by Nader Shah’s Ashfarid dynasty. Nadir came from the border area of Persia/Afghanistan and his version of the Persian Empire extended deep into Afghanistan, covering Herat, Kandahar, and even Kabul. Again, I haven’t seen or read anything explicitly describing 19th Century Afghan tribal or regular troops carrying this flag, but that doesn’t mean it never happened.

(11) Below is a Persian/Iranian flag used during the siege of the Afghan city of Herat in 1838 . It bears another Arabic phrase from the Koran (Surat As-Saf 61:13) طر من الله و فتح لقريب – which roughly translates to: “With help from Allah victory is near” or “Victory from Allah and an imminent conquest”. The Afghans were the enemy of the Persian Muslims flying this flag, but it’s possible that Afghan Muslims from the same region used the same Koranic phrase on their own flags:

TURKMEN (aka: TURCOMAN) of Afghanistan:

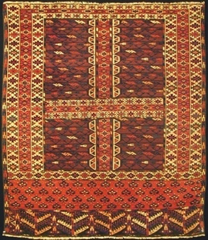

(12) Another ethnic minority that contributed discrete units of troops to 19th Century Afghan armies are the TURKMEN of Balkh and Herat. Here are a couple of Turkmen flags. First is the modern flag of Turkmenistan used from 1992-1997, featuring “carpet” patterns of the country’s 5 main tribes; second is the “Herat Uprising” flag used by civilian rebels and mutinous army troops in the city of Herat during their rebellion against the Afghan communist government (9 months before the Soviet invasion), which has the Arabic inscription: “God is Great”. Both have a 1:2 ratio:

(13) Note: More Afghan Turkmen flags might feature a single tribal carpet pattern throughout:

TEKE:

YOMUD:

ARSARY/ERSARY:

Now we get to the era of flags described in the opening scholarly essay in this way:

In the reign of Amir Dōst Moḥammad (1819-63) and Šēr ʿAlī Khan (1863-79; see AFGHANISTAN x) there existed triangular, red and green military flags bearing the words of the Islamic confession of faith (šahāda) as well as the names of the four caliphs and verses from the Koran relating to jehād “holy war,” all in white color.

(14) Here are some versions of the Shahada in Arabic calligraphy:

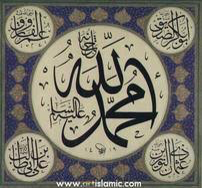

(15) Here are some versions of the names of the Four Caliphs in Arabic calligraphy:

(16) We now reach the era of the Second Afghan War (1878-1880). The only contemporary image I know that shows a flag/standard of the Afghan regular army is this one below showing an Afghan regular cavalryman on horseback wearing a triangular flag strapped to his back, in similar fashion to a Japanese Sashimono. Unfortunately the decoration/insignia/inscription on the flag is indistinct. The darker marks on the flag may be meant to represent shadows on a solid color flag, or perhaps the flag bore an inscription of some kind, such as the Shahada:

It is certain that the rider in the above illustration (by R.C. Woodville, Jr.) is a member of an Afghan regular cavalry unit. This is a sketch that was made in black-&-white and then colorized by someone who had only a general knowledge of the uniforms in question rather than specific knowledge of the particular subject. The cavalry trooper’s uniform jacket should almost definitely be RED, as there are definitive contemporary records of Afghan regular cavalry troopers in the same style of uniform but with the jackets in RED. I believe since the British cavalry giving chase in the background themselves wear red tunics, the Afghans ended up in blue.

An element present in many/most Afghan Tribal and some regular flags (including the cavalry one just above) is FRINGING around the edges. Almost all the triangular Afghan flags seen in photos and drawings/paintings have FRINGE on all edges other than the hoist (the edge adjacent to the flagpole). Sometimes the fringe is the same color as the flag itself and other times it’s a contrasting color.

(17) Finally we reach the flag adopted by the “Iron Amir” ABDUR RAHMAN KHAN. He negotiated with the British during the later stages of the Second Afghan War and they agreed to recognize him as ruler and withdraw from the country towards the end of 1880. He ruled from 1880 until his death in 1901 and his flag was SOLID BLACK:

(18) In 19012 his son Nabibullah added a pretty cool insignia to the black flag, as seen here:

It could be cool to use versions of this flag, or take elements from this flag, and use them for Afghan regular army standards. The wreaths, the crossed gun barrels, the triangular flags flying from poles, the mosque, and the Royal headgear/crown – these elements used in different combinations could be placed on solid black fields or green or red or even white fields. Such flags could be carried by Afghan troops during the Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919. They would be pure conjecture, but informed by legitimate Afghan insignia of the time.

(19) Here’s a later version of the flag emblem from 1919-1926:

The crown is raised a bit higher, making it easier and clearer to make out the building below it as a MOSQUE. The somewhat triangular old school Afghan flags remain, but the crossed gun barrels have been replaced by crossed swords. Again, these elements could be used to create some cool standards for Afghan regular army units. These would be entirely speculative if used by Afghan regulars of the Second Afghan War or before, but more potentially legitimate for post-1880 regulars of Abdur Rahman’s army, and possibly legitimate for Afghan regulars in the Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919.

(20) Here’s a description and photo of a tribal flag artifact donated by an Englishman to the Muger Memorial Library of Boston University: “Stored away in the Department of Special Collections is a curious-looking triangular banner, faded and a bit stained, with an assortment of symbols appliqued onto alternating bands of red and white. Supporting documents reveal that the artifact is a standard once carried into battle by a Waziri tribesman near the border of Afghanistan and what is now Pakistan in the late 19th century.”

It’s a frustrating photo since the flag is not fully unfurled, but the description and matching visual of RED AND WHITE STRIPES is definitely useful. The cross shapes are a bit perplexing but it turns out such crosses have a presence in Turkish, Persian & Afghan rugs as a “protective motif offering protection against evil, catastrophes or ill will.”

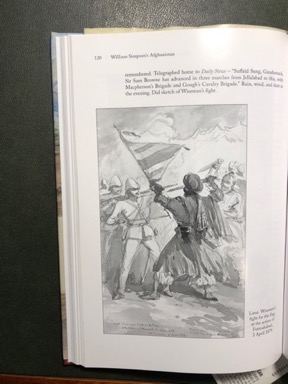

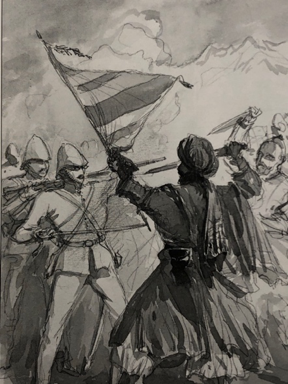

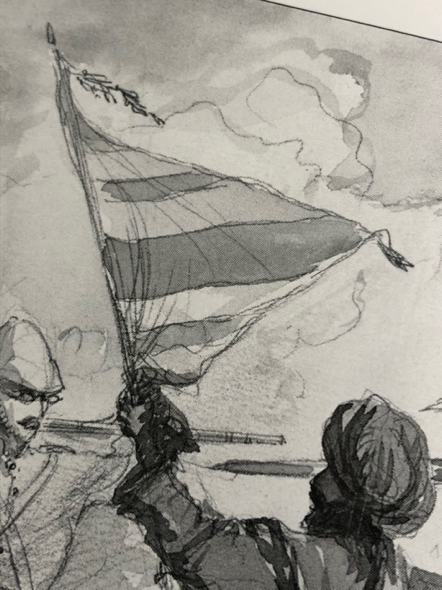

(21) Drawing by William Simpson of Lt. Wiseman’s death at the April 2nd 1879 Battle of Futtehebad:

William Simpson was a “Special Artist” who covered the Second Afghan War from 1878 to 1879 for the Illustrated London News. A book of his Afghan War art and the diary he kept while creating it was published in 2016. During his two years “embedded” with the British and Indian forces he created some of the best and most accurate visual records of the war.

The British officer pictured with the sword is Lt. Wiseman of the 17th Leicestershire Regiment of Foot. Wiseman KIA by sword cuts to his head while attempting to capture the flag shown in the drawing, during the April 2nd, 1879 battle of Futtehabad (AKA: Fatehabad). After the British won the battle Simpson spoke with Wiseman’s surviving comrades-in-arms to get details re: what the flag looked like, as Wiseman gave his life but failed to take it, so Simpson couldn’t see the flag itself. Major Wigram Battye, a very popular and higher ranking officer of the Guides Cavalry (he may even have been in command of the regt. at the time, while their Colonel was away serving as a brevet Brigadier General) was also KIA at Futtehabad, and his death received much more attention both in the press and later in the history books. Maybe if Wiseman has succeeded in capturing the enemy flag before he was killed, his death would have made more of a mark. In Simpson’s diary he says he heard about Wiseman’s death and then interviewed some of Wiseman’s comrades who fought in the battle and saw him fight for the flag and die, to get more information on what it looked like. This seems like the closest thing possible to photographic or eyewitness testimony RE: the appearance of the flag. Also, after looking at the illustration again, I was struck by how the wide and narrow stripes may be in TWO DIFFERENT COLORS, a darker color for the wide and a lighter (but still darker than the very light background) color for the narrow stripes. I assume the background would be white, but it could also be yellow, or a pale shade of green or blue. The same book has watercolor versions of some of Simpson’s Afghan drawings, but it seems he never got around to painting a color version of this one, unfortunately.

The flag is carried by a tribesman on foot, but it’s also shaped like the Afghan Regular Cavalry triangular flag. It’s also HORIZONTALLY STRIPED with a single thick stripe across the middle, and thin stripe above and below, with small areas of that same darker color (whatever it may be) at the top and bottom triangular corners. It also has THREE Moghul-like LONG TASSELS dangling from each corner of the triangle, including I believe the bottom one where it meets the pole, where I believe the tassels can be seen dangling over the left hand of the Tribesman holding it. It appears to be a relatively small flag on a relatively small pole.

One last interesting detail about this flag is that the look of the dark stripes on the white (or some other lighter shade) background of this flag is very reminiscent of the flag shown in #19 in this doc.

(22) Tribal Flags from the 1897 Mohmand Campaign:

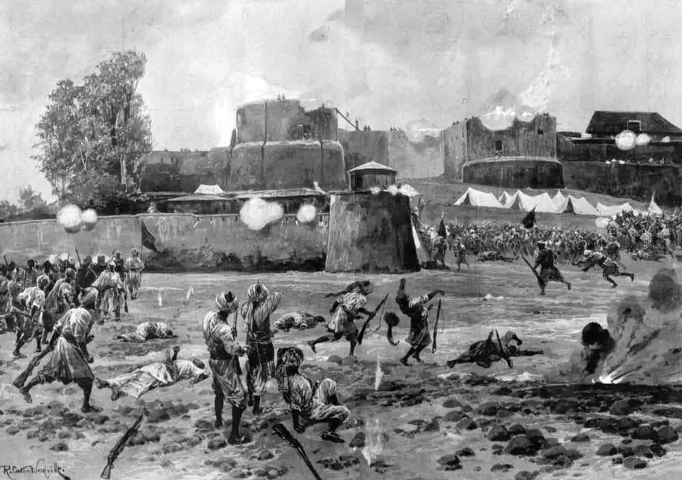

a. 1897 Mohmand Campaign – Tribal Attack on Shabkadar Fort by Sir Richard Caton Woodville, Jr, famous British painter and war artist known for visual accuracy:

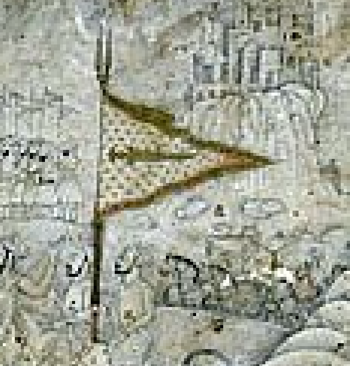

- b. 1897 Mohmand Campaign – 13th Bengal Lancers charging Tribesmen at Shabkadar by Major Edmund Hobday, R.A., who served during the campaign. NOTE that in the CU you can see how this flag with its apparently white background and dark stripes is reminiscent of both the photo #19 and the Simpson drawing #20:

CU of Tribal Flags:

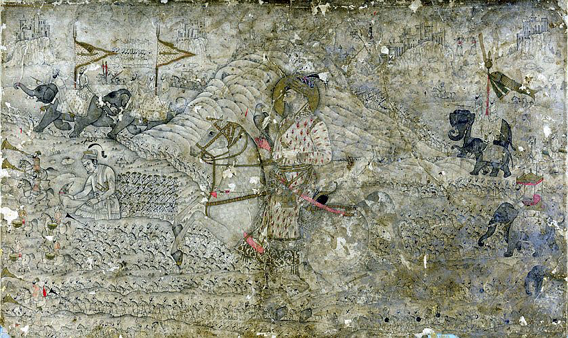

(23) This next-to-last flag comes from Shah Jahan, the fifth Moghul Emperor, who ruled modern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan from 1628 to 1658. It’s a bit of a precursor to the Durrani black flag with white sword emblem, but on a triangular flag. Though is no proof of its use by Afghan tribesmen or regulars, Shah Jahan and his army left their mark on Kabul, Kandahar, and other parts of Afghanistan, and it’s a cool looking flag:

CLOSE-UP of Shah Jahan flag:

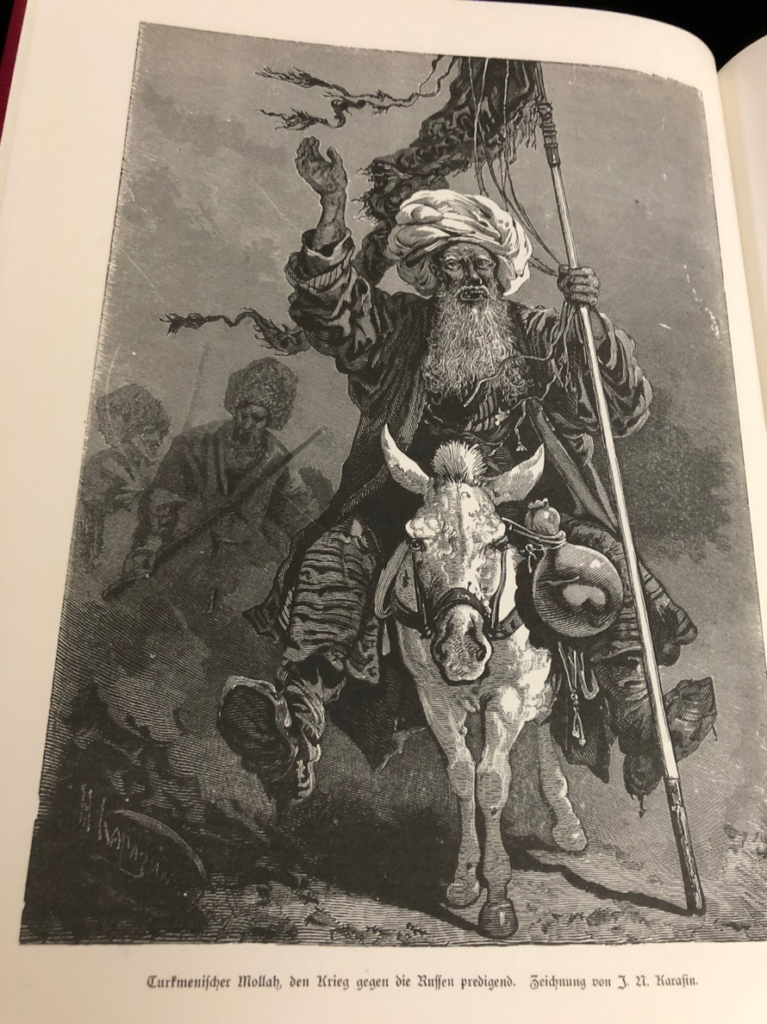

(24) The German book “Afghanistan” written & illustrated by Dr. Hermann Roskoschny, Leipzig 1885, reprinted in 2011 under one cover with the same author’s book on “Russian Central Asia”, has a few illustrations of Afghan & Turkmen flags:

a. “Turkmen Mullah preaching war against the Russians” – Drawing by J.N. Karafin:

b. “Escorts in combat with Turkmen” – Detail of mounted Turkman standard-bearer:

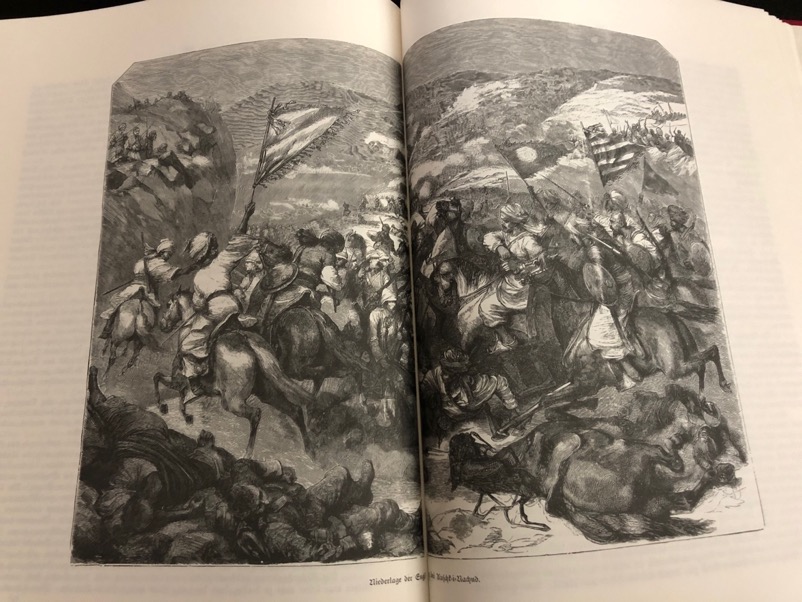

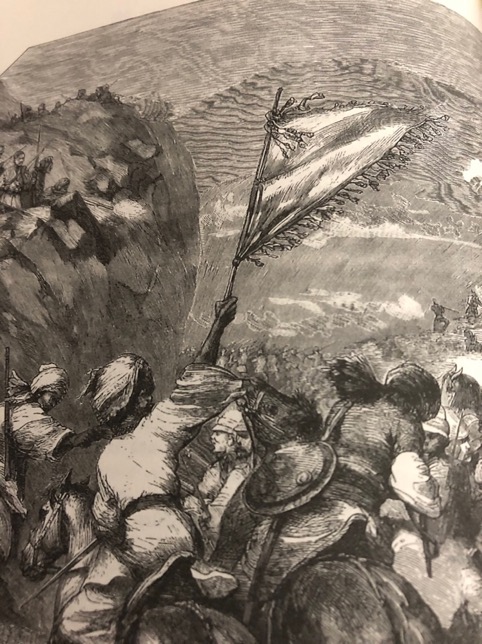

c. “Defeat of the British at Khushk-i-Nakud” – This refers to the Battle of Maiwand, which was fought 8 miles North of Khushk-i-Nakud:

Close-Up details d & e from above illustration; NOTE all 4 flags are TRIANGULAR and at least 3 of the 4 are FRINGED:

d.

e.

(25) Last is a collection of Afghan national flags dating from the Durrani Empire until today, which includes some of the flags discussed

Click on the “Download” LINK above to download a PDF file of all the above info

What an amazing piece of research. Highly enjoyable and motivational. I can’t wait to create more 2nd Afghan War tribal flags utilizing your posted references. I’m looking forward to pursuing the posts on your new blog.

You’ve become the resident expert and “Go To Guy” of all things for the 2nd Afghan War!

Cheers my friend.

Jeff!!! Hope appropriate that the first comment left on this site should be from you, my friend! I myself can’t wait to see those flags of yours! On a related note, THANKS for the flag for Ayub Khan’s command tent. I installed it on the tent the other night and it looks great and is the perfect size!

Wow, most thorough. Thanks for all of the information .

My pleasure, John, thanks for taking the time to leave your comment!

A thorough and interesting post and what a nice welcome to the new home!

Best Iain

Glad you enjoyed it, Iain! It’s highly motivational to hear from visitors who enjoyed what gets posted here!

A lot of information here what a great collection in one place.

A wee test Ethan to see if the comment goes through this time.

Hope you and yours are safe and well.

Best wishes

Willie

Willie my friend,

Sincere apologies for the long delay in approving your post! Things have been hectic between family life and prepping for the Kandahar 140 game, and I just logged on to administer this site after too long of a delay. Hopefully you’ll be kind enough to leave more comments in the future and I’ll be more on top of things! We are all doing okay. Thank you for the kind wishes for my family, which I send back to you for your own.